Speaking for Yourself: A Core Practice in Dialogue Therapy for Couples.

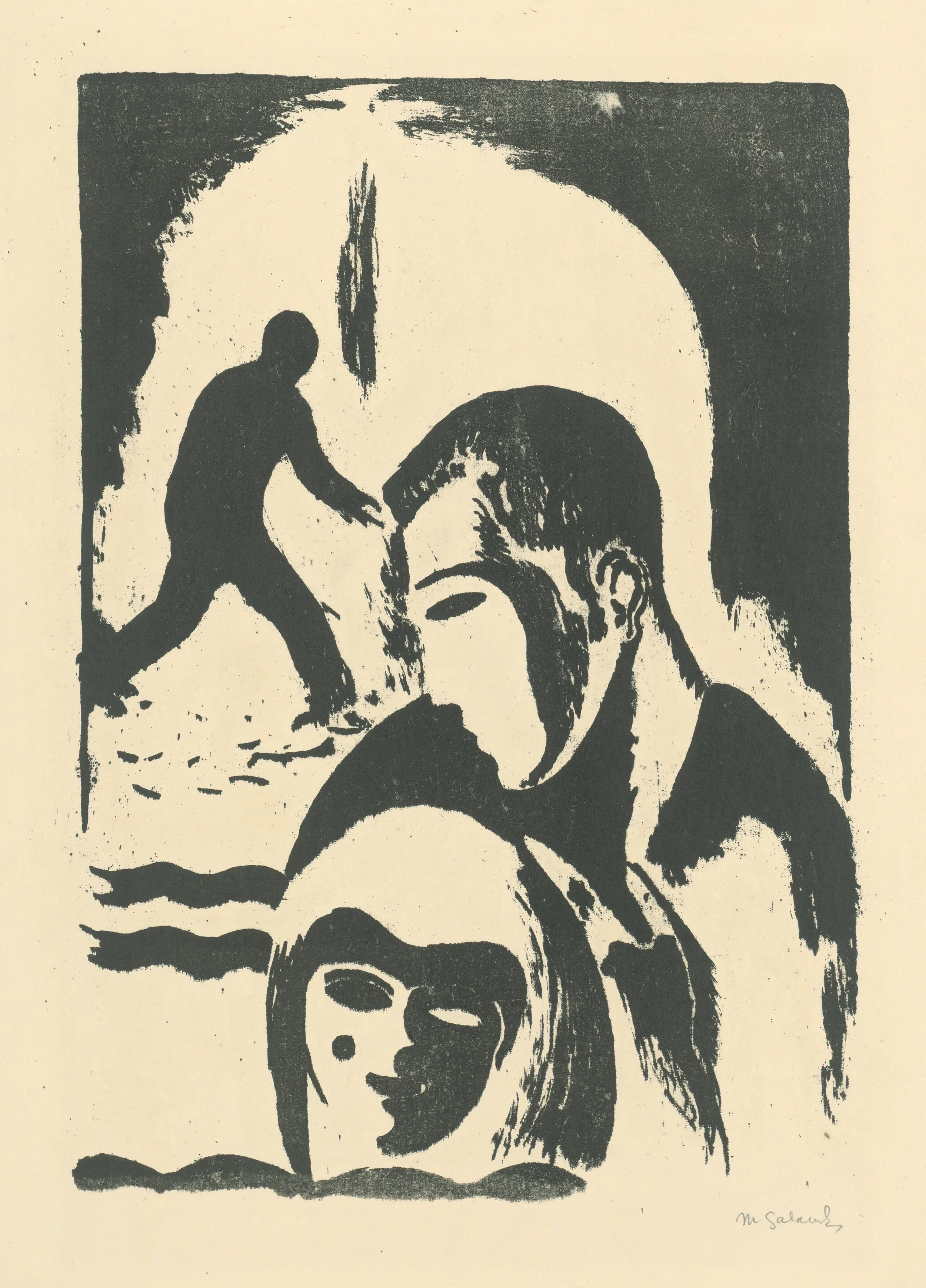

Lovers by Mikuláš Galanda.

One of the most quietly radical ideas in couples therapy is also one of the simplest: speak for yourself. In Dialogue Therapy, this principle is not merely a communication skill—it is the ethical and emotional backbone of the work.

Many couples arrive in therapy locked in a familiar loop. One partner speaks about the other (“You always…,” “You never…”), while the other becomes defensive, withdrawn, or counterattacks. What appears as conflict on the surface is often something more tender underneath: a longing to be seen, a fear of being dismissed, or an early attachment wound being activated (Johnson, 2019).

Dialogue Therapy interrupts this cycle by asking partners to return to their own inner ground.

What Does “Speaking for Yourself” Mean?

In Dialogue Therapy, speaking for yourself means taking responsibility for your own experience—your thoughts, emotions, bodily sensations, memories, and meanings—without attributing intention, motive, or character to your partner (Young-Eisendrath, 2019).

Instead of:

“You don’t care about me,”

the speaker is invited to say:

“I notice I feel lonely and hurt when we don’t spend time together, and I find myself telling a story that I don’t matter.”

This shift may seem subtle, but it is profound. When partners speak from the “I,” they move out of accusation and into self-revelation. Rather than prosecuting a case, they are offering testimony from their own inner life.

Why This Matters in Intimate Relationships.

Research on couples therapy consistently shows that blame and criticism escalate physiological arousal and defensiveness, making genuine listening nearly impossible (Gottman & Levenson, 2000). Speaking for oneself reduces reactivity and increases emotional safety by allowing the listener to stay present rather than preparing a rebuttal.

Dialogue Therapy rests on the assumption that no one can fully know another person’s inner world. When partners assume intent—often shaped by past relational injuries—misunderstandings multiply. Speaking for yourself restores humility to the relationship: this is my experience; I am still learning about yours (Pieniadz & Young-Eisendrath, 2020)

Over time, this practice strengthens autonomy within intimacy. Rather than collapsing into fusion (“If you change, I’ll be okay”) or distancing (“I don’t need you anyway”), partners learn to stand in their own emotional truth while remaining connected—an essential capacity for secure attachment (Bowlby, 1988).

Speaking for Yourself and Attachment Patterns.

For many couples, difficulty speaking for oneself is rooted in early attachment experiences. Those who learned that expressing needs led to rejection may silence themselves, while others—who had to amplify distress to be noticed—may speak urgently, critically, or with emotional flooding (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016).

Dialogue Therapy does not pathologize these patterns. Instead, it helps partners recognize them with curiosity and compassion, creating space for choice rather than reflex. By slowing the conversation and emphasizing mindful speech and listening, couples become aware not only of what they say, but how they say it—tone, pacing, volume, and bodily cues all become part of the dialogue (Siegel, 2012).

Dialogue Therapy as a Practice, Not a Performance.

Originally developed by Polly Young-Eisendrath and Ed Epstein, Dialogue Therapy is a time-limited, skills-based approach designed to help couples become experts in their own relationships. Rather than depending on the therapist to mediate conflict, couples learn a structured, repeatable dialogue process they can use outside the therapy room (Pieniadz & Young-Eisendrath, 2020).

At the heart of this structure is speaking for yourself—paired with mindful listening. One partner speaks from lived experience; the other listens without interruption, correction, or defense. Over time, difference becomes less threatening, and conflict transforms from rupture into a source of relational learning.

From Reactivity to Relationship.

Speaking for yourself does not mean being passive, overly careful, or emotionally distant. It means being clear: clear about what you feel, clear about what matters, and clear about where you end and your partner begins.

In clinical practice, this clarity often restores dignity on both sides of the relationship. Partners feel less misunderstood and more respected—not because agreement is guaranteed, but because experience is honored.

Intimacy deepens not when we get the other person to change, but when we risk being known.

And that risk begins by speaking for yourself.

Notes.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books.

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (2000). The timing of divorce: Predicting when a couple will divorce over a 14-year period. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(3), 737–745.

Johnson, S. M. (2019). Attachment theory in practice: Emotionally focused therapy (EFT) with individuals, couples, and families. Guilford Press.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2016). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Siegel, D. J. (2020). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Young-Eisendrath, P. (2019). Love between equals: Relationship as a spiritual path. Shambhala Publications.

Pieniadz, J., & Young-Eisendrath, P. (2020). Dialogue therapy for couples and real dialogue for opposing sides (1st ed.). Routledge.

Make it stand out

If you and your partner find yourselves stuck in familiar cycles of misunderstanding or reactivity, couples therapy can offer a structured, compassionate way forward. I invite you to reach out to explore whether Dialogue Therapy—grounded in mindful communication and emotional responsibility—may support deeper understanding and reconnection in your relationship. You don’t have to solve everything at once; beginning the conversation is often the most meaningful first step.

Lisa A. Rainwater, PhD, MA (couns), LCMHC, CCMHC, CCTP, CT is a depth psychotherapist and founder of Rainwater Counseling in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Licensed in North Carolina, Colorado, and Wisconsin, she works with individuals, couples, and groups.

Lisa worked for five years as a psychosocial oncology counselor at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist, where she supported patients, families, caregivers, and providers navigating cancer, loss, and end-of-life transitions. She is a Certified Dialogue Therapist for Couples, Certified Thanatologist, Certified Clinical Trauma Professional, and Eagala-Certified Equine Assisted Psychotherapist, integrating psychoanalytic, mindfulness-based, and experiential approaches to foster healing and reconnection.

Holding a PhD in German and Scandinavian Studies from the University of Wisconsin–Madison and a master’s in Counseling from Wake Forest University, Lisa’s work bridges mythology, depth psychology, and existential meaning-making. She recently completed Finding Ourselves in Fairy Tales: A Narrative Psychological Approach at Pacifica Graduate Institute and continues advanced studies through the Centre for Applied Jungian Studies.

She is licensed to practice in North Carolina, Colorado, and Wisconsin.